Abstract

Aim: The main objective of this study was to explore the relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies of farmers and their financial performance.

Setting: The study was conducted in South Africa among farmer clients of a commercial financial organisation.

Methods: The financial performance of the farmers was calculated by means of financial ratios which were used to compile a single performance indicator: operating efficiency. The operating efficiency indicator was calculated using a financial-based data envelopment analysis. An entrepreneurial competencies instrument was used to measure the entrepreneurial competencies of the farmers. Ordinary least squares regression was used within the principal component regression framework to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and financial performance.

Results: The results indicate there is a positive relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and financial performance of farmers. Each of the individual competencies also indicated positive correlation between the entrepreneurial competencies and financial performance.

Conclusion: An increase in specific entrepreneurial competencies behaviour may increase the operating efficiency of the farm. Educational opportunities exist to educate farmers on the potential benefits of using entrepreneurial behaviour to their advantage (to benefit their operating efficiency). Sectors involved with agriculture, for example agricultural advisors, financial advisors and educational institutes, should emphasise the importance of utilising the competencies of farmers.

Introduction and background

Agriculture is one of the most important sectors within the South African economy, as it contributes to the economy in terms of employment, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and rural development, among others. In 2015, the direct contribution of primary agriculture to the South African GDP was 2.1% (Statistics South Africa 2015). Agriculture also provides employment, especially within rural areas, creating job opportunities for the educated and uneducated populations of the South African labour force. The agricultural sector also creates opportunities for domestic growth, employment expansion and foreign exchange income. Taking these opportunities into consideration, a focus on expanding the agricultural sector (i.e. growth, business integration and employment) is thus expected to contribute significantly towards growing the economy of South Africa.

Increasing costs, for example production costs or operating costs, within the South African agricultural sector have been limiting growth opportunities. Increasing input prices within the agricultural sector, together with decreasing commodity prices, have created a cost price squeeze in agriculture (ABSA 2015). The cost price squeeze puts the profitability of farmers under increased pressure. In addition to shrinking profit margins, farmers also face increased pressure to produce more in order to survive within a volatile market. The price volatility and underfunding from financial institutions have placed more pressure on farmers to become innovative within their farming business to increase performance (Asfaha & Jooste 2007). Therefore, farmers need to be innovative to ensure that their farming enterprises remain profitable and competitive within the dynamic environment.

A farm’s performance is measured by how successful it is within the market and is determined by financial and non-financial measurements. Non-financial measurements include employee growth, job satisfaction, self-sufficiency and so forth (Walker & Brown 2004). Financial performance is focused on minimising costs, increasing business growth and sustainability to increase profitability. There is a link between a farm’s financial performance and the skills of the manager or owner, creating a need for improved decision-making skills (Man, Lau & Chan 2002). The decision-making ability of an entrepreneur has been identified as being an important skill for gaining profitability and increasing business success.

An entrepreneur is a person who takes more risks, provides capital within the business, is innovative and has the ability to seek opportunities in order to increase profits (Bergevoet 2005). To achieve business success, a farmer needs to make strategic, as well as innovative, decisions concerning all levels of the business. Therefore, farmers rely on entrepreneurial competencies and characteristics to enable them to become more successful. The topic of entrepreneurial competencies has increased in popularity as a way for determining entrepreneurial behaviour among individuals. Man et al. (2002) identified competencies that line up with the literature on which characteristics an entrepreneur needs to have in order to exhibit entrepreneurial behaviour. The entrepreneurial competencies, linked with behaviour and decision-making skills, have been proven to positively influence the financial performance of a business.

The topic of entrepreneurial competence has received little attention in the context of financial performance, despite the fact that profit margins are under pressure in the agricultural sector and the view that entrepreneurial skills are expected to have a positive influence on decision-making. However, the importance of entrepreneurial skills for sound business decision-making is evident from literature (e.g. Ketelaar-de Lauwere, Enting, Vermeulen & Verhaar 2002; Bergevoet 2005). The link between entrepreneurship and financial performance is reflected in the decision-making abilities of the farmer, and this topic has received little attention from researchers in the context of decision-making in agriculture.

Financial performance in agriculture, however, has received ample attention over the last few decades. Swenson (2003) explains that financial records are set in a structured format that allows producers to summarise their financial information so that it eases the decision-making process. Researchers have focused on increasing profit (production) by decreasing costs (input costs). This means that a farming business needs to pursue liquidity and profitability to improve its financial performance (Sebe-Yeboah & Mensah 2014). Therefore, recommendations centre around improving the financial performance through increasing both liquidity and profitability. This is, however, done by making sound business decisions, which requires some level of entrepreneurial skills.

Researchers have explored the relationship between entrepreneurial skills and technical efficiency of farms in South Africa (Jordaan 2012; Jordaan & Grové 2012). A positive relationship was found and recommendations were made to place more emphasis on extending the entrepreneurial skills of smallholder farmers to improve their performance. However, to this researcher’s knowledge, little to no research has been done proving the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies of farmers and their financial performance in a South African context.

The main objective of this study is to explore the relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies of farmers and the financial performance of their farms in order to determine whether entrepreneurial characteristics positively influence the financial performance of the farm. To achieve the objective, financial performance of the farmers was determined by making use of financial ratios in the following categories: liquidity, solvency, profitability and financial efficiency. To measure the entrepreneurial competencies of farmers, the entrepreneurial competency instrument developed by Man (2001) was used.

Methodology

Data

The research is based on financial data of clients from a commercial financial organisation in South Africa, and a questionnaire survey administered to measure entrepreneurial competencies of the respondents.

The financial data were obtained from credit application forms by the clients. As per the formal agreement between the authors and the financial organisation, all data were treated as confidential and no information or interaction was allowed between the authors and clients. All information was received from relationship executives (bankers) from the financial organisation. To protect the clients, the executive representatives replaced all client names with respondent numbers before submitting the data to the authors. This was to ensure the anonymity of their clients. The financial organisation kept track of the respondents and their corresponding respondent numbers. Respondent numbers allowed the financial organisation’s executive representatives to complete the entrepreneurial competency instrument according to the respondents.

The entrepreneurial competencies instrument (Man 2001) was completed by executive representatives of the financial organisation who work closely with the clients, and who assisted the clients with their credit applications. The survey was conducted between July and November 2015. From a possible 160 respondents1 available for the research, 99 questionnaires were completed and returned to the researcher. Only 94 of the 99 respondents had sufficient financial data and entrepreneurial competencies data required for inclusion in this research.

Measuring financial performance of respondents

Financial performance measures

The ratio measures were used to quantify the financial performance for the respondents. Ratio measures eliminate the economies of size (currency values), thereby making it possible for different farms to be compared against one another (Henning, Strydom & Willemse 2011). The financial measures used in this research are shown in Table 1.

| TABLE 1: Measures of financial performance according to ratios used in the study |

In the study four financial measures were used to determine the financial performance of respondents. Liquidity measures the ability of the farm to meet financial obligations, while solvency measures the ability of the farm to repay debt if all the assets are sold. Profitability is used to measure how the farm is generating profits and financial efficiency is a measure of how efficiently capital is used on the farm. These four financial measures are used to determine the operating efficiency score. The financial-based data envelopment analysis (DEA) model is used to determine an operating efficiency score for each farm to be used as the dependent variable in the regression analysis.

Deriving a single financial performance indicator

Specification of the DEA model to quantify financial performance as operating efficiency: The adapted financial ratio-based DEA model provides an indication of the efficiency of the farms by considering multiple financial ratios simultaneously and providing a single measurement of operating efficiency. According to Henning, Strydom, Willemse and Matthews (2013), every farm is seen as a decision-making unit (DMU), which is a term for the assortment of firms or departments that have the same goals and objectives, using the same inputs and outputs to reach their goals (Al-Shammari & Salimi 1998). The financial ratio-based DEA model combines multiple financial measurements into a single operating efficiency (Henning et al. 2013).

The output-orientated financial ratio-based DEA model, with variable returns to scale, is defined as:

Z0 specifies the ratio expansion rate for DMU0 and λn represents the multiplier weights used to determine the efficiency frontier (Henning et al., 2013). The total number of DMUs is represented by N and is judged on m which represents the financial measurements (Al-Shammari & Salimi, 1998). ri0 represents the total number of observed measurements for DMU0. The mathematical model is calculated and solved for every individual farm, thereby calculating the relative operating efficiency for every DMU (Ablanedo-Rosas, Gao, Zheng, Alidaee & Wang 2010). The interpretation of the Z0 value can be confusing; therefore, to ease the interpretation, an interpretable efficiency score (a) was estimated (Henning, 2011; Henning et al. 2013). The higher the Z0 value (estimated ratio expansion rate), the lower the efficiency level will be. The efficiency score (a) allows for the ranking of DMU0 or the current DMU. The efficiency score of 1 is considered to be efficient and a score less than 1 is inefficient (Ablanedo-Rosas et al. 2010).

The efficiency score (Eqn 5) determined with the financial ratio based DEA model will be used in determining the relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies of farmers and their financial performance.

Measuring entrepreneurial competencies

Instrument used to explore entrepreneurial competencies

The instrument used to measure the entrepreneurial competencies was developed by Man (2001). The instrument consists of 53 statements related to the abilities of an individual (as an owner or manager of a business) that are used to measure 10 competencies as determined by Man. The statements are answered on a seven-point anchored Likert scale, where 1 is ‘strongly disagree’ and 7 is ‘strongly agree’ with the respective statement.

Nieuwoudt (2016) explains in detail the 10 entrepreneurial competencies identified by Man (2001). These competencies are: opportunity competencies, relationship competencies, conceptual competencies (analytical competencies and innovative competencies), organising competencies (operational competencies and human competencies), strategic competencies, commitment competencies, learning competencies and personal strength competencies.

Determining the entrepreneurial competencies

Following Man (2001), factor analysis (FA) was used to determine the entrepreneurial competencies. Byrant, Yarnold and Michelson (1999) summarise that factor analysis is a multivariate statistical procedure that is used to decrease a large number of variables into a smaller set of variables (factors). This establishes underlying dimensions between measured variables and latent constructs and it provides construct validity evidence of reporting scales (Byrant et al., 1999). When making use of FA, Tinsley and Tinsley (1987) mention that the minimum number of cases per item must be at least five. However, there remain different opinions on the exact number of cases per item. The research therefore followed the procedure of Man, where items were divided into three categories as discussed at a later stage. The analysis was performed with a varimax rotation, Kaiser normalisation and principal component analysis (PCA). Statements included in the determined components had to fulfil certain criteria, described below.

The first step is to determine the communalities. The communality value for each statement should be 0.50 or higher or the statement should be removed. Once communalities with a value less than 0.50 have been removed, the factor loadings determine the variables included in each component. Costello and Osborne (2005) suggest that a factor loading of 0.50 is enough to be considered ‘strong’. However, if there are cross-loadings between components, the statement should be removed. Lastly, components with an eigenvalue greater than 1 are included in accordance with the Kaiser-Guttmann rule (Fekedulegn, Colbert, Hicks & Schuckers, 2002; Williams, Brown & Onsman, 2012).

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of sampling adequacy (KMO) indicates the degree of variance and the KMO value needs to be above 0.49. The Bartlett test of sphericity is statistically significant if the value is less than 0.001. A Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7 or higher will confirm that there is an existing strong internal consistency between the items measuring each of the related competencies. Man (2001) divided the entrepreneurial competencies instrument into three distinct parts, namely Q01–Q17, Q18–Q40 and Q41–Q53. All of the criteria above were applied to the factor analysis of the three parts of the entrepreneurial competencies instrument, following the procedure of Man.

Exploring the influence of entrepreneurial competencies on financial performance

Regression analysis was used to explore the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and financial performance of the respondents. The dependent variable in the regression analysis is a vector of efficiency scores estimated to represent the level of financial performance of the respondents, making use of the ordinary least squares (OLS) regression approach within principal component regression (PCR). McDonald (2009) argues that the properties of OLS, parallel those of OLS in the linear probability binary discrete choice model. OLS estimates of β are consistent and asymptotically normal under general conditions. Following the recommendation of McDonald, the dependent variable in this research is the logarithm of the financial efficiency scores calculated in the DEA model.

A correlation matrix (Table 2) was calculated for all the independent variables, namely the entrepreneurial competencies. From the correlation matrix it was evident that multi-collinearity is present between the independent variables (due to all the correlation coefficients being less than 0.9). The multi-collinearity supports the use of the PCR model for determining the relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies and operating efficiency.

| TABLE 2: Correlation matrix for entrepreneurial competencies |

The PCR is a data analysis tool that is used to reduce the dimensionality (number of variables) of a large number of interrelated variables, while retaining variation. PCR offers the chance to discover the most significant directions among data and to eliminate ‘noise’ directions. PCR offers new filtered information on an orthogonal or even orthonormal basis (Pfisterer 2006). This new set of information is known as eigenvectors and eigenvalues. Therefore, because of orthogonality, the eigenvectors are uncorrelated and the basic vectors corresponding to the maximum variance can be extracted without distracting the analysis in other directions (Pfisterer 2006).

Principal component regression

The application of the PCR here is based on Magingxa (2006) and Khaile (2012).

Estimating principal components: In order to calculate the PCR, the eigenvectors of the variables need to be calculated; the vectors can be used to construct the principal components (PCs). The decisive factor for determining which factors needed to be included in the model (components) is an eigenvalue greater than 1. This method is known as the Kaiser-Guttman rule (Fekedulegn et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012). Very small eigenvalues indicate that there is severe multi-collinearity; therefore, small eigenvalues are removed from the analysis (Liu, Kuang, Gong & Hou 2003). The statistical analysis program SPSS 23.0 (SPSS 2015) is used to determine the eigenvectors and eigenvalues from the original independent variables. A correlation matrix is used to determine eigenvalues φ1, φ2, … … …, and equivalent eigenvectors vj, making use of standardised and non-standardised variables. The following Equations 6 and 7 are used to determine the eigenvalues and eigenvectors:

Eigenvectors are organised to create the matrix shown in Equation 7. V is acknowledged to be orthonormal, because V columns act in agreement with the conditions  and and  for ≠ j: for ≠ j:

The important step in this section is the extraction of components. The common rule for selecting principal components is to select those with eigenvalues greater than 1.

Regression with principal components: The principal components scores denoted by Σ are calculated by matrix multiplication of eigenvalues. These eigenvalues were obtained from Equation 7. Therefore, the next equation describes the principal components’ Σ scores as follows:

In Equation 8, As is the n × k matrix of the variables. V is eigenvector matrix as determined in Equation 7. The component Σ scores are calculated in a matrix multiplication product form, with a dimension of k components equal to k variables. The evaluation of the components is regressed against the original dependent variable a. This is where Equation 9, the linear unit model, is presented as:

AsV and ε are independently distributed with zero means, 0 ≤ yi ≤ 1, with the limit point yi = 1 possessing positive probability. Also,  and Bs are estimated by the OLS model, and are standardised coefficients for the constant and the independent variables respectively. Since the eigenvectors are orthogonal to one another, as defined by the eigenvector matrix V where VV′ = I, Equation 9 can be reformulated in the form: and Bs are estimated by the OLS model, and are standardised coefficients for the constant and the independent variables respectively. Since the eigenvectors are orthogonal to one another, as defined by the eigenvector matrix V where VV′ = I, Equation 9 can be reformulated in the form:

Or

Σ = AsV and ρ = V’Bs. Σ is the n × l matrix of the retained components, V is a k × l matrix of eigenvectors equivalent to the l retained components and As is the standardised dependent variables (Magingxa 2006). ρ is an l × l vector of new coefficients associated with l components. Standard errors of the estimated coefficient ρ as symbolised by an l × 1 vector are calculated in the form of (Fekedulegn et al. 2002; Magingxa 2006):

is the variance of the residuals that were calculated in Equation 10. The elimination of some principal components does not change the magnitude of the variance (Fekedulegn et al. 2002). However, the elimination of one or more components will ultimately reduce the total variance, resulting in a better model. The elimination of components can be done based on their significance from the regression results (Magingxa 2006). Presume that r principal components are eliminated due to insignificance; then Equation 11 can be reformulated to use k – r components. is the variance of the residuals that were calculated in Equation 10. The elimination of some principal components does not change the magnitude of the variance (Fekedulegn et al. 2002). However, the elimination of one or more components will ultimately reduce the total variance, resulting in a better model. The elimination of components can be done based on their significance from the regression results (Magingxa 2006). Presume that r principal components are eliminated due to insignificance; then Equation 11 can be reformulated to use k – r components.

The 0 symbol on ε0 is used to differentiate it from ε determined in Equation 11. The residuals differ because the vectors of coefficients have been reduced to k – r components.

Identifying the significance of individual explanatory variables within the principal components: The advantage of a PCR exercise is that all hypothesised independent variables can be manually calculated. The recollected components are transformed back into the original independent variables:

Vk – r is the matrix of eigenvectors for the retained principal components,  is a vector of coefficients (except for the intercept) estimated in Equation 13 and is a vector of coefficients (except for the intercept) estimated in Equation 13 and  is a vector of coefficients (except for the intercept) of the parameters in vector βs estimated in Equation 10. Variance of the principal component estimators in the form of standardised variables is calculated by: is a vector of coefficients (except for the intercept) of the parameters in vector βs estimated in Equation 10. Variance of the principal component estimators in the form of standardised variables is calculated by:

indicates the squares of the eigenvector elements of indicates the squares of the eigenvector elements of  in Equation 7 and Ks indicates the squares of the elements of the matrix of standard errors of the coefficient matrix ρ in Equation 13. The equivalent standard errors for the estimators of principal components of standardised variables are specified by: in Equation 7 and Ks indicates the squares of the elements of the matrix of standard errors of the coefficient matrix ρ in Equation 13. The equivalent standard errors for the estimators of principal components of standardised variables are specified by:

In the same context as Fekedulegn et al. (2002) and Magingxa (2006), standardised variables  are transformed back to natural non-standardised variables bj.pc of Ai. The results are given by: are transformed back to natural non-standardised variables bj.pc of Ai. The results are given by:

sai is the standard deviation of the ith original variable Ai and  are coefficients of the standardised variables. The original non-standardised dependent variable (efficiency score) is used in the OLS model when estimating principal component significance. It therefore follows that the natural non-standardised variables bi.pc can be correctly calculated when the standard deviation sai is calculated by 1/Sai as shown in Equation 18. are coefficients of the standardised variables. The original non-standardised dependent variable (efficiency score) is used in the OLS model when estimating principal component significance. It therefore follows that the natural non-standardised variables bi.pc can be correctly calculated when the standard deviation sai is calculated by 1/Sai as shown in Equation 18.

Results

Operating efficiency as indicator of financial performance

The operating efficiency scores are restricted to an interval between 0 and 1, where a farm with a score of 1 is considered to be efficient, and a score below 1 is considered inefficient. An important aspect to remember is that the operating efficiency scores are determined in comparison with the other farms in the sample. The weights, determined with the DEA model, for each farm differ from one another in such a way that the individual farm’s performance compares the farm’s highest efficiency score to the other farms (Henning 2011). The efficiency scores of the farms are calculated relative to one another and an inefficient score indicates that a farm has room for improvement relative to the more efficient farms.

Each farm’s operating efficiency has the highest possible score for the financial data used, and this score is used to compare the other highest possible scores of the other farms included in the study. Farms that are identified as being efficient are the ones with the highest possible scores from the given financial measurements, as explained in the methods. Therefore, the reason for farms being calculated as inefficient is due to the farm not performing as effectively in the financial measurements as a farm that has been calculated to be efficient.

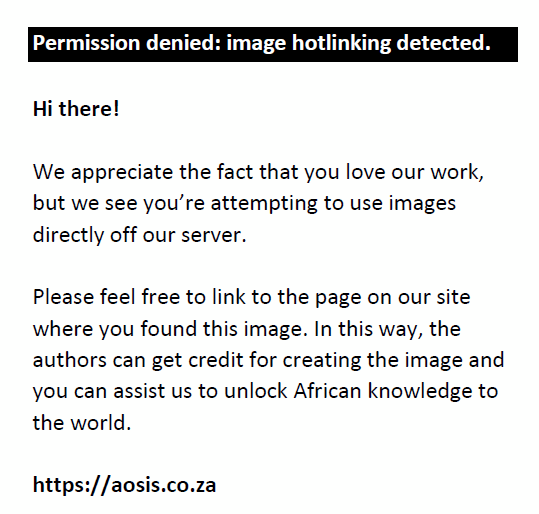

The results from the operating efficiency measures exhibit a range of operating efficiency scores, ranging between 0.749 and 1. The distribution skews towards the right with a very high average operating efficiency of 0.877. An inefficient score (i.e. a score less than 1) is only an indication that the farm is less efficient when compared with the efficient farms in the study (Henning et al. 2013). The cumulative distribution of the operating efficiencies indicated the spread of the efficiency scores between 0.749 and 1, as shown in Figure 1.

|

FIGURE 1: Cumulative probability distribution of operating efficiencies for the farmers. |

|

An operating efficiency score of 1 indicates that the farm is efficient; in the study 13 (13.82%) of the farms were calculated as being efficient. Therefore, the remaining sample farms (inefficient farms) were compared to the efficient farms. From Figure 1, it is evident that 50% of the farmers have efficiency scores of below 0.855, where an efficiency score of 0.855 indicates that compared to other farms in the study the majority of the farms are operating at 85.5% level of efficiency. An 85.5% level of operating efficiency indicates that a farm with this score is only achieving 85.5% of the financial performance potential compared to an efficient farm in the same sample.

In Figure 1, three distinct inclines in the inefficient groups are observed. Between the operating efficiency scores of 0.749 to 0.810, a sharp incline of the operating efficiencies is experienced. The next group of operating efficiency scores has a steady incline from 0.820 to 0.900. Lastly, from 0.910 to 0.999 there is a sharp incline between the operating efficiencies. Nieuwoudt (2016) identifies that the financial measurements used to determine the operating efficiencies of the farms contribute to the different scores for each farm. When determining the financial ratios of farms the ratios are divided into three groups, namely ‘vulnerable’, ‘stable’ and ‘strong’. These three groups contribute to the different inclines seen in Figure 1, highlighting the more effective use of financial measures on the farm to ‘better’ perform among the rest of the sample.

When the financial measures of an inefficient farm are compared to an efficient farm, the efficient farms financially performed ‘better’ in comparison to an inefficient farm. Nieuwoudt (2016) explains the financial ratio score distribution for efficient farms and inefficient farms. Taking the financial ratios ratings into consideration the overall ratings of the efficient farms were rated more ‘strong’ compared to the inefficient farms that rated more ‘stable’ or ‘vulnerable’, thus explaining why these farms are considered efficient and inefficient respectively (Nieuwoudt 2016).

In the next section, the entrepreneurial competencies of the farmers are explored. An entrepreneurial competency score is calculated for each farmer, which is then used to determine the influence of each of the competencies on the financial performance (operating efficiency) of the farmers.

Entrepreneurial competencies

Identifying the entrepreneurial competency of respondents

The results from the PCA are used to determine the specific competencies, as well as the statements that are significant in determining these competencies. The three parts of the factor analysis are done following the procedure of Man (2001) and also applied by Henning (2016). The first part, factor analysis for Q01 to Q17, is grouped as ‘interaction and exploring’; the second part, factor analysis for Q18 to Q40, is grouped as ‘business management’ and the last part, factor analysis for Q41 to Q53, is grouped as ‘personal improvement’. The group names for the three factor analysis parts are in accordance with Henning (2016).

Interaction and exploring: The factor analysis for statements Q01 to Q17 consists of three components. Statements Q04, Q05 and Q09 had communality below 0.50, and they were therefore removed, while Q10, Q12 and Q14 were removed due to cross-loadings. The level of significance for the Bartlett’s test of sphericity is less 0.001, thereby indicating the factor analysis to be significant. The KMO value, 0.847, is greater than 0.49 and thus the factors are significant.

In Table 3, the rotated component matrix indicates the statement with high factor loading in three components. The components have eigenvalues greater than 1, and the overall cumulative percentage of variance for all three components explains 70.11% of the variance. Each of the three components identified has a Cronbach’s alpha greater than 0.7 confirming that there is strong existing internal consistency between the items that relate to the individual competencies.

| TABLE 3: Rotated component matrix for interaction and exploring components |

The first component with high factor loadings is for statements Q15, Q17, Q11 and Q16. The statements relate to the abilities of farmers to form ideas that can be implemented in their farming business. Q11 relates to the farmers’ ability to apply innovative ideas, knowledge and issues in new ways. Because agricultural markets are volatile and agricultural products are dependent on weather conditions, farmers need to think and apply new ideas to ensure success. Q15, Q16 and Q17 deal with looking at old problems in new ways, finding new ideas and treating problems as opportunities. This is essential in the unpredictable sector of agriculture. As the component relates to the conceptualising abilities of the farmers, the component was named conceptual competencies.

The statements with high factor loadings in the second component are Q06, Q07, Q08 and Q13. Q06 and Q07 are related to negotiating and interacting. For farmers, it is important to be able to negotiate the best price for crop or livestock (even though a farmer is a price-taker, benefits or extras can be negotiated), while still being able to maintain good business relationships with processors. Thus, this links with Q08, which is related to maintaining a personal network of work contacts. However, in order for farmers to grow their business, they need to take reasonable risks in terms of their crop production, deliveries, which producers they sell to and which companies they buy inputs from. This relates to Q13 (job-related risks) having a high average score, where farmers assess and take risks to increase business size and profitability. Therefore, this cluster of competencies relates to communicating abilities and relationships, and accordingly it will be called relationship competencies.

The last component consisted of high factor loadings for Q01, Q02 and Q03. Q01 is related to identifying goods specifically needed in the agricultural market, while Q02 and Q03 are more related to consumer needs. The focus of these statements is on seeking or identifying gaps and needs within the market. These needs and gaps represent possible business opportunities for farmers. Therefore, the last component is called opportunity competencies.

Business management: Three components were extracted for statements Q18 to Q40. The Bartlett’s test was less than 0.001 and the KMO value, 0.873, was greater than 0.49. In the test for communalities, none of the statements needed to be removed. In order to determine the components, the component structure was used and cross-loadings for Q20, Q21, Q26, Q29, Q30, Q33, Q37, Q38 and Q39 were identified. These statements were removed accordingly and the factor loadings are reported in Table 4.

| TABLE 4: Rotated component matrix for business management components |

As shown in Table 4, the eigenvalues for each component are greater than 1 and the cumulative percentage of variance for all three components explains 65.43% of the total variance. The strategic component had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.907, the operational component had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.861 and the commitment component had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.760. The Cronbach’s alpha values above 0.7 confirm that there is strong existing internal consistency between the different items.

The first component consists of eight statements with high factor loadings, namely Q26, Q28, Q31, Q32, Q34, Q35, Q36 and Q40. In terms of setting, aligning and determining the costs and benefits of strategic goals, Q32, Q35 and Q36 are needed. For farmers, strategic goals are needed to ensure that they achieve the long-term goals determined for their farming business. Farmers need to plan for the future, due to factors outside their control affecting their production, crop rotation, land rotation and so on, which are all factors for long-term planning. Q28 relates to the long-term planning required to avoid problems by identifying them beforehand, as well as identifying opportunities. To achieve these opportunities, commitment is needed, which is measured by Q40. The last statement that plays a role is Q26, which relates to motivating people. To achieve long-term goals is to motivate the people who will help the farmer achieve goals. This component relates to the strategic planning of business activities and is therefore called strategic competencies.

Q18, Q19, Q20, Q21, Q22 and Q23 are the statements with high factor loadings in the second component. Q18 and Q19 are concerned with the planning of operations, and the organisation of the business and resources. This is important as farmers need to determine what they are going to produce, what resources they need to have available, how they will utilise the resources, what tasks need to be completed and how they will ensure that the tasks run as smoothly as possible. This all relates to Q20, Q21 and Q23. However, in order to ensure the smooth running of tasks, a farmer needs to supervise employees to make sure tasks are completed in a correct and timely manner. As the statements are related to the daily operations of the farming business, the component was named operational competencies.

High factor loadings for statements Q37 and Q38 were determined in the third component. Q37 is related to how dedicated the farmer is to see the venture work and Q38 to the refusal to see the venture fail. This indicates that farmers are very committed in seeing their ventures succeed and this component was therefore called commitment competencies.

Personal improvement: According to the factor analysis for Q41 to Q53, all the contributing factors for the appropriateness of factor analysis were sufficient for the Bartlett’s test and latent root test. The KMO value, 0.913, is above 0.49 indicating a sufficient degree of variance. The test for communalities indicated no communalities with values below 0.5. In the component structure test, statements Q48, Q50 and Q52 were removed due to cross-loadings. The factor loadings are reported in Table 5.

| TABLE 5: Component matrix for personal improvement component |

In Table 5, the component with factor loadings above 0.5 for each statement, the eigenvalue and percentage variance for the component are shown. The component has an eigenvalue greater than 1, and the cumulative percentage of variance for the component explains 58.66% of the total variance. The Cronbach’s alpha indicates that there is internal consistency between the statements.

All the statements with high factor loadings, Q41, Q42, Q43, Q44, Q45, Q46, Q47, Q49, Q51 and Q53, are only one component. Q41, Q42, Q43, Q44 and Q45 relate to farmers keeping up-to-date in their field of business by making proactive decisions to learn and apply the relevant skills and knowledge. Due to the rapid expansion in agricultural technologies, this is a critical part of farming. Changing weather and climate patterns, together with increasing input costs, force farmers to apply new skills so as to enable them to continue producing. Q51 states that a farmer should be able to identify his or her strengths and weaknesses to match them with opportunities and threats, which also relates to Q53 in recognising shortcomings and finding ways to work on them. Farmers need to employ knowledgeable advisors where they have shortcomings, should they are not able to learn the skills needed. Maintaining a positive attitude and high energy levels will help with learning and adapting a new skill into day-to-day living, so that the skill can be mastered. This is essential in an expanding market. Q46, Q47 and Q49 all measure the level of optimal performance required to be successful. The factors included in the component relate to the capabilities of the farmers to encourage confidence and deal with difficulties; thus this component is called support competencies.

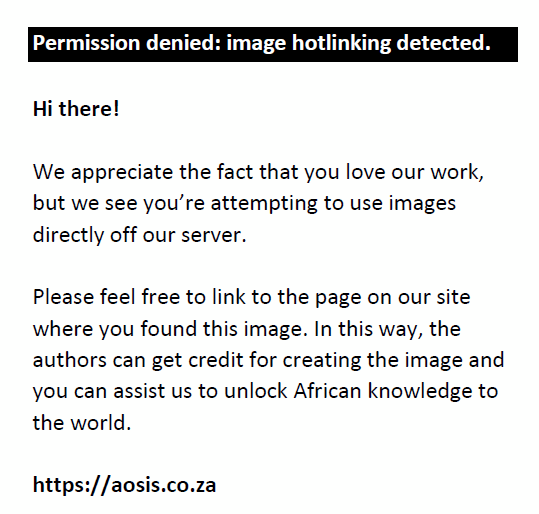

Entrepreneurial competencies scoring: Figure 2 shows the distribution of the entrepreneurial competencies identified by the factor analysis of the farmers between the lower, mean and upper values. The lower and upper values are indicated by the lines to show the spread, while the histogram indicates the mean values of the competencies. In order to make the figures easier to interpret, the average scores were converted into percentages in order to compare the different competencies with each other.

|

FIGURE 2: Distribution of scores for entrepreneurial competencies among the farmers |

|

Figure 2 shows that all of the competencies identified for the farmers are near the upper bound (higher end of the distribution), with all of the average scores being above 70%. The weakest average score identified is in opportunity competencies, indicating the greatest room for improvement lies there. Commitment competencies (91%) represent the strongest competencies identified, followed by operational competencies (87%). Both of these competencies have average scores above 85%, which still leaves room for improvement.

As the opportunity scores are higher, this is an indication that the farmers’ behaviour does indeed illustrate that they are actively seeking new opportunities. These new opportunities can be used as strategies to increase their market, production, efficiency or to decrease production costs, thus positively benefiting their financial performance. The results correspond with the literature, where Vik and McElwee (2011) state that in the changing agricultural markets, the identification of new opportunities is an essential requirement for farmers. However, compared with the other entrepreneurial competencies, opportunity competencies has the lowest average score, indicating room for improvement through identifying new opportunities, such as vertical or horizontal integration in the market, or decreasing input costs by searching for new vendors.

In terms of the relationship competencies, the average scores for the farmers were above 80%, illustrating that the farmers’ behaviour is tending towards negotiating, interactions and personal networks with others, as well as showing their ability to take reasonable job risks. The use of these relationship behaviours in their day-to-day business may open doors to new opportunities in terms of reasonable risk, as well as improving the farmers’ abilities to negotiate. Farmers are considered to be price-takers, although they are still able to negotiate the terms of delivery or transport cost to ensure that they receive the most out of their product. This links with interacting with others and creating a personal network.

The higher scores for the conceptual competencies highlight the fact that the farmers think conceptually about how they analyse problems. This indicates that a farmer’s behaviour reflects the focus on his or her decision-making ability. The results indicate that farmers do indeed have the ability to analyse, assess and react to situations. Problems can occur at different stages in the dynamic agricultural sector and farmers need to take their time in thinking about what they need to achieve and what decisions need to be made in order to achieve their goals. Thus, the farmers conceptualise the way they think about and analyse problems. This relates to the literature where conceptual thinking is concerned with decision-making in regard to innovation, risk, problems and seeking possible solutions.

Operational competencies relate to the way a farmer organises his or her business operations. These competencies form part of the underlying competencies of organising competencies, which are directly aimed at the operational part of organising. The high average score greater than 85% indicates that the farmer’s behaviour is focused on the operations of the business. Most farmers are ‘hands-on’ with the day-to-day running of the business, which links to why these competencies have a high score. Farmers need to be present in coordinating tasks and making sure that the appropriate resources are used in order for the tasks to be completed correctly. Therefore, this behaviour indicates that the strategy of the farmer is to ‘run’ the farm.

Strategic competencies have an average score greater than 75%, thereby illustrating that farmers are actively setting, evaluating and implementing strategies on their farms that relate to organising and operational competencies. Because strategic competencies relate to the implementing of strategies, it is expected that farmers have higher scores, as this determines whether or not they reach goals and increase sales, thereby increasing profitability.

Commitment competencies scored the highest average score of all the competencies. This illustrates that the farmers’ behaviour is mostly orientated towards seeing that any venture they take on is successful. As the agricultural market is very volatile, this behavioural aspect is a necessity in order to guarantee success. Commitment competencies are the factors that encourage entrepreneurs to start, grow or expand their businesses. For farmers, this is an important aspect due to farmers mostly being owners as well as managers, meaning that the farmers are responsible for a wide variety of tasks, spread over a wide area.

Support competencies rated an average score greater than 75%, meaning that the farmers’ behaviour suggests that they do use these competencies, but there is still room for improvement. This grouping of competencies is based on how farmers, as entrepreneurs, see their own strengths and ability to adapt and learn. The average score is closer to the upper score, indicating that the majority of farmers are rated high in their ability to learn and adapt. This links with the unpredictability and volatility of the market of the agricultural sector, where crops and livestock may be lost due to factors outside a farmer’s control, through drought or disease, for example. Farmers accordingly need to be able to adapt in order to survive.

The following section evaluates the influence of each of the entrepreneurial competencies on the efficiency scores of the farmers.

Entrepreneurial competencies influence on financial performance

The non-standardised data were imported into SPSS (statistical software) to obtain eigenvalues and eigenvectors. The eigenvectors calculated are needed to compute the PCs. An un-rotated procedure of components was selected to compute the eigenvalues and eigenvectors. This method was chosen because the components were not the primary objective.

The PCs were calculated through a matrix multiplication between the variables and the eigenvectors. Thus, uncorrelated PCs were manually calculated. A correlation matrix was used to determine whether any correlation exists. Table 6 shows the eigenvalues of the components selected for the regression at the production stage. Two of the variables were removed in the determining of the PCs due to commonalties less than 0.50.

| TABLE 6: Eigenvalues for entrepreneurial competencies efficiency regression model. |

Following the Kaiser-Guttmann rule, only one PC was extracted, since only one had an eigenvalue equal to or greater than 1 (Fekedulegn et al. 2002; Williams et al. 2012). PC1 explained 72.69% of the variation in the underlying variables. To determine the significance of the identified variable (ZPC1) on operating efficiency, an OLS model was estimated. The result of the regression analysis, as calculated with SPSS, shown in Table 7, indicates that entrepreneurial competencies index is significant with a very small positive coefficient. A positive value indicates that if entrepreneurial competencies increase, operating efficiency will also increase, as was expected.

| TABLE 7: Significant principal component for the operating efficiency. |

Evidence from literature indicates that an increase in entrepreneurial competencies will increase the financial performance (operating efficiency). The relationship between the operating efficiency and entrepreneurial competencies is, however, very small, indicating that the entrepreneurial competencies as a whole (all the competencies combined into one index) have a very small positive effect. A possible reason might be that a farmer is trying to over-commit in all aspects measured in terms of competencies, thereby neglecting the focus on individual competencies. Therefore, a more in-depth look into the individual competencies is needed to determine the effect of the individual entrepreneurial competencies on operating efficiency.

However, if farmers concentrate on their individual competencies, they will be able to identify where they are lacking and then make use of necessary measures to counter this. Accordingly, the management of a farm requires that the farmer should be competent in all of the competencies. This increases the need to concentrate on the competencies that need to be focused on individually in order to ensure that the competition for a farmer’s time and effort is directed towards increasing the competencies where he or she is lacking. This is, however, difficult if all the competencies are grouped together, creating a small positive relationship between competencies and operating efficiency.

T-tests were used to test the significance of the correlation between each of the individual entrepreneurial competencies scores and operating efficiency scores, making use of simetar. The results of the t-tests are shown in Table 8.

| TABLE 8: Results from the t-test of the relationship between entrepreneurial competencies and operating efficiency. |

The correlation coefficients of each of the competencies in relation to the operating efficiency score indicate that there is a positive correlation between the competencies and the operating efficiency. However, the relationship competencies and operational competencies are statistically non-significant. Each of the competencies has an individual positive relationship with operating efficiency, even though when combined in the group of entrepreneurial competencies there is a very small positive value. Therefore, the focus should be on individual competencies and not necessarily on entrepreneurial competencies as a whole.

The opportunity competencies indicate that those farmers who are actively seeking new opportunities in order to increase farm business, ways to integrate other sectors in the market, new gaps within the market, or even opportunities to decrease production costs, will be able to increase their operating efficiency in a positive way. The farmers’ average score for these competencies showed the lowest score for all of the competencies, indicating the largest room for improvement. Thus, if farmers were to expand their businesses horizontally or vertically within the value chain, they would increase the size of their businesses, thereby creating more revenue opportunities within the businesses. The increase in income could improve the profitability of the farming business. Thus, actively seeking opportunities can benefit the operating efficiency of a farm.

The conceptual competencies of farmers are also expected to have a positive influence on their operating their farms efficiently. These competencies are closely related to opportunity, which presents the innovative ideas or knowledge needed to think of problems in new ways. However, this group of competencies achieved the second-lowest average score, indicating more room for improvement. Usually, the need to seek an opportunity arises owing to problems or lack of a solution. Thus, if farmers become innovative with their problem-solving efforts, this might create opportunities for new products or services within the market. For example, if a farmer decides to plant maize instead of farming with livestock, he will need a combine harvester, and although this is an expensive implement, the farmer could make the combine available for hire to other farmers facing the same need, thereby helping with the payments for the implement. This could increase the farmer’s income and help decrease the debt used to acquire the implement, while being innovative and seeking a new opportunity.

Strategic competencies can increase the operating efficiency of the farm in a positive way, when there is a focus on increasing the farmer’s strategic competency behaviours. The competencies focus on setting and determining the cost–benefits for reaching strategies or goals. Thus, if a farmer has a well-planned business strategy with a clear vision and mission, he or she will be able to determine the short-term, reachable goals that will determine the success of the business plan. If a farmer, for example, endeavours to increase the production area of crops in each planting season, while maintaining the same input costs, he will be able to grow the business and increase income at the same time. This will, however, require commitment to the goal in order to achieve success.

The average score for commitment competencies was the highest among all the competencies. If there is an increase in how committed the farmer is in ensuring that a venture is successful, the operating efficiency will increase. The positive relation between commitment and operating efficiency is similar to that described in literature, which suggests that being committed to the business will ensure business growth. If there is an increase in the business size or opportunities, there will be an increase in income. For any goal or strategy to be achieved, is important that there be a commitment to the strategy, with belief in own capabilities to achieve strategy. This links with the support competencies of a farmer.

The support competencies are the competencies with the largest relation with operating efficiency, when there is an increase in this group of competencies behaviour. These competencies are closely related to the personal strengths and learning capabilities of the farmer. Self-efficacy is important in order for farmers to believe in their own capabilities to learn and apply new knowledge and to be successful in their operations. If a farmer has a higher belief in him or herself, he or she will be willing to work harder and be more committed in seeing a venture through. If a farmer does not believe in his or her own capabilities in terms of crop knowledge, he or she will doubt him or herself and not commit to ensuring the success of the crop. This might decrease the production yield, thereby negatively effecting operating efficiency. In the literature review, it is suggested that to ensure an increase in business growth, farmers should constantly increase their knowledge, thereby increasing their self-efficacy and self-belief.

Conclusion

For the original problem identified, there was no or little evidence available in South Africa that proved that entrepreneurial competencies may contribute to the improvement of the financial performance of farmers. The literature suggests that a positive relationship exists between financial performance and higher levels of entrepreneurial competencies. Therefore, the objective of this study was to explore the relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies of farmers and the financial performance of their farms in order to determine whether entrepreneurial characteristics positively influence the financial performance of the farm.

The results of this research showed a positive relationship between operating efficiency and the entrepreneurial competencies for the farmers included in the research. A positive value indicates that if entrepreneurial competencies increase, operating efficiency will also increase, as was expected. A positive relationship was, however, very small for the entrepreneurial competencies index. Further investigation was done to determine the individual relationship between each of the entrepreneurial competencies and the operating efficiency. The results showed that each of the individual entrepreneurial competencies have a positive relationship with the operating efficiency. Therefore, an increase in specific entrepreneurial competencies behaviour may increase the operating efficiency of the farm.

Entrepreneurial competencies, as a whole, indicate that a farmer needs to focus on several competencies at the same time, in consequence of which certain competencies will be neglected. Farmers need to be owners, managers and workers, at the same time, which creates an increased demand on the farmer to perform well on several levels within the business. However, if farmers concentrate on individual competencies, they will be able to identify where they are lacking and make use of necessary measures to counter this. Therefore, the management of a farm means that a farmer needs to be competent in all of the competencies.

From the individual entrepreneurial competencies analyses, it was identified that the farmers scored the strongest for the commitment competencies and the operational competencies. However, operational competencies were non-significant with regard to the operating efficiency. Commitment competencies on the other hand were significant at a 5% level of significance, thus emphasising the importance of commitment. Commitment competencies are the factors that encourage entrepreneurs to start, grow or expand their business; as the agricultural market is very volatile, this behavioural aspect is a necessity in order to guarantee success.

Opportunity competencies had the lowest score among the farmers, indicating room for improvement. The opportunity competencies are farmers who are actively seeking new opportunities in order to increase farm business, ways to integrate other sectors in the market, new gaps within the market, or even opportunities to decrease production costs. Vertical and horizontal integration are only two of the factors identified that farmers can use to increase their opportunity competencies, but by using value chain integration as a negotiation tool, farmers will combine conceptual competencies with their opportunity competencies. To achieve the factors mentioned, strategic planning will be needed, thus highlighting the importance of the strategic competencies of the farmers.

Educational opportunities exist to educate farmers on the potential benefits of using their entrepreneurial behaviour to their advantage. The focus should be on educating farmers on ways to integrate the business (vertically or horizontally), planning and evaluating their opportunities as well as committing to the success of the venture. Sectors involved with agriculture, for example agricultural advisors, financial advisors and educational institutes, should emphasise the importance of utilising the competencies of farmers.

It is important to note that the focus of this study is based on a specific group of farmers, with a small sample. The farmers in this study have diverse farming practices and they produce differing products. Therefore, the variability in efficiency scores can be influenced by these factors. Research can be repeated to confirm the results of the procedure, due to the small sample size. Further research can be done to investigate and explore different alternative measures in determining the entrepreneurial competencies.

Acknowledgements

This work is based on research supported in part by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa by the grant Unique Grant No. 94132. Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors and the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationship(s) that may have inappropriately influenced them in writing this article.

Authors’ contributions

S.N. was the principle researcher involved in all stages of the research and wrote the article. J.I.F.H. assisted with conceptualisation and writing of the article and provided financial assistance through the NRF grant for the research as well as supervision to the main researcher. H.J. assisted with conceptualisation and writing of the article and provided supervision to the main research.

References

Ablanedo-Rosas, J.H., Gao, H., Zheng, X., Alidaee, B. & Wang, H., 2010, ‘A study of the relative efficiency of Chinese ports: A financial ratio-based data envelopment analysis approach’, Expert Systems 27(5), 349–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0394.2010.00552.x

ABSA, 2015, Agricultural outlook 2015, viewed 02 December 2012, from www.agrisa.co.za/pdf/Absa_Eng.pdf

Al-Shammari, M. & Salimi, A., 1998, ‘Modeling the operating efficiency of banks: A nonparametric methodology’, Logistics Information Management 11(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1108/09576059810202196

Asfaha, T.A. & Jooste, A., 2007, ‘The effect of monetary changes on relative agricultural prices’, Agrekon 46(4), 460–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.2007.9523781

Bergevoet, R.H.M., 2005, ‘Entrepreneurship of Dutch dairy farmers’, Doctoral thesis, Wageningen University, The Netherlands.

Byrant, F.B., Yarnold, P.R. & Michelson, E., 1999, ‘Statistical methodology: VIII. Using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in emergency medicine research’, Academic Emergency Medicine 6(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1999.tb00096.x

Costello, A.B. & Osborne, J.W., 2005, ‘Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis’, Practical Assessment. Research & Evaluation 10, 1–9, viewed 05 March 2015, from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=10&n=7

Fekedulegn, B.D., Colbert, J.J., Hicks, R.R., Jr. & Schuckers, M.E., 2002, Coping with multicollinearity: An example on application of principal components regression in dendroecology, Research Paper NE-721, USDA Forest Service, Newtown Square, PA.

FFSC, 2011, Financial guidelines for agricultural producers, Farm Financial Standards Council, Menomonee Falls, WI.

Henning, J.I.F., 2011, ‘Financial benchmarking analysis: Northern Cape farmers’, Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State.

Henning, J.I.F., 2016, ‘Credit scoring model: Incorporating entrepreneurial characteristics’, Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

Henning, J.I.F., Strydom, D.B. & Willemse, B.J., 2011, ‘Developing a financial ratio benchmarking system for GWK district farmers in South Africa’, in 18th International Farm Management Congress, Methven, New Zealand, viewed 13 August 2015, from http://ifmaonline.org/wpcontent/uploads/2014/08/11_Henning_etal_P366-379.pdf

Henning, J.I.F., Strydom, D.B., Willemse, B.J. & Matthews, N., 2013, ‘Financial measurements to rank farms in the northern cape, South Africa, using Data Envelopment Analysis. Developing a financial ratio benchmarking system for GWK district farmers in South Africa’, in 19th International Farm Management Congress, Warsaw, Poland, viewed 13 August 2015, from http://ifmaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/13_Henning_etal_P141-151v3.pdf

Jordaan, H., 2012, ‘New institutional economic analysis of emerging irrigation farmers’ food value chains’, Doctoral dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

Jordaan, H. & Grové, B., 2012, An economic analysis of the contribution of water use to value chains in agriculture WRC Report: No 1779/1, p. 12, Department of Agricultural Economics, University of The Free State, Bloemfontein.

Ketelaar-de Lauwere, C., Enting, I., Vermeulen, P. & Verhaar, K., 2002, ‘Modern agricultural entrepreneurship’, International Farm Management Association, 13th Congress, Wageningen, The Netherlands, July 7–12, 2002, pp. 1–17.

Khaile, P.M.E., 2012 ‘Factors affecting technical efficiency of small-scale raisin producers in Eksteenskuil’, Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein.

Lans, T., Verstegen, J. & Mulder, M., 2011, ‘Analysing, pursuing and networking: Towards a validated three-factor framework for entrepreneurial competence from a small firm perspective’, International Small Business Journal 29(6), 695–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610369737

Liu, R.X., Kuang, J., Gong, Q. & Hou, X.L., 2003, ‘Principal component regression analysis with SPSS’, Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 71, 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2607(02)00058-5

Magingxa, L.L., 2006, ‘Smallholder irrigators and the role of markets: A new institutional approach’, Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State.

Man, T.W.Y., 2001, ‘Entrepreneurial competencies and the performance of small and medium enterprises in the Hong Kong services sector’, Doctoral dissertation, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Man, T.W.Y., Lau, T. & Chan, K.F., 2002, ‘The competitiveness of small and medium enterprises: A conceptualization with focus on entrepreneurial competencies’, Journal of Business Venturing 17(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(00)00058-6

McDonald, J., 2009, ‘Using least squares and tobit in second stage DEA efficiency analysis’, European Journal of Operational Research 197, 792–798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2008.07.039

Nieuwoudt, S., 2016, ‘Entrepreneurial characteristics and financial performance’, Master’s dissertation, University of the Free State.

Pfisterer, H.-C., 2006, Data-based modelling of electroless nickel planting, Department of Automation and Systems Technology, Control Engineering Laboratory, Helsinki University of Technology, Helsinki, Finland.

Sebe-Yeboah, G. & Mensah, C., 2014, ‘A critical analysis of financial performance of Agricultural Development Bank (ADB, Ghana)’, European Journal of Accounting Auditing and Financial Research 2, 1–23.

SPSS, 2015, IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 23.0, IBM Corp, New York.

Statistics South Africa, 2015, GDP fact sheet 4th quarter, viewed 24 November 2015, from http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0441/Fact_Sheet_1_4q_2015.pdf

Swenson, A.L., 2003, Financial characteristics of North Dakota: 2000–2002, Agribusiness and Applied Economics Report no. 522, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND.

Tinsley, H.E. & Tinsley, D.J., 1987, ‘Uses of factor analysis in counseling psychology research’, Journal of Counseling Psychology 34(4), 414.

Vik, J. & McElwee, G., 2011, ‘Diversification and the entrepreneurial motivations of farmers in Norway’, Journal of Small Business Management 49(3), 390–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00327.x

Walker, E. & Brown, A., 2004, ‘What success factors are important to small business owners?’, International Small Business Journal 22(6), 577–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242604047411

Williams, B., Brown, T. & Onsman, A., 2012, ‘Exploratory factor analysis: A five-step guide for novices’, Australasian Journal of Paramedicine 8(3), 1.

Footnotes

1. Although the information concerning the farmers was obtained from representatives of the financial organisation, the farmers are referred to as ‘respondents’ for ease of reference, where appropriate.

|